A lot of ink has been spilled lately on how stablecoins pose a significant threat to the banking sector. Nic Carter and many others have talked about the rise of narrow banking with stablecoins – essentially institutions that take in deposits but do no lending, just invest the deposits in treasuries. There has been discussion of deposit flight as individuals and businesses seek higher yield opportunities via stablecoins vs. traditional bank deposits. While I believe stablecoins and the underlying blockchain infrastructure they run on offer a leapfrog moment for financial infrastructure, I’ve been generally more skeptical about this deposit flight narrative.

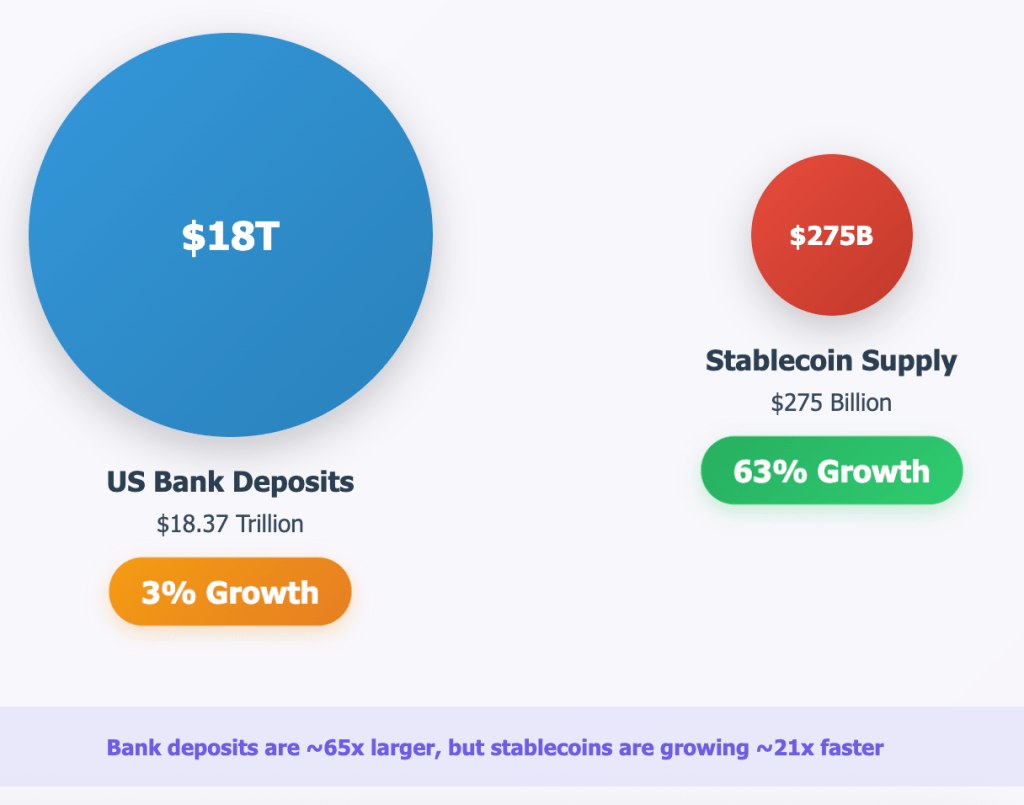

Today, banks in the US hold over $18T in deposits. The entire global circulating stablecoin volume is just shy of $300B. Obviously, stablecoin supply is still miniscule in comparison (less than 2% of US bank deposits), but the rapid growth rate in the supply and tangible use cases of stablecoins for payments starting to be seen have caused bank executives to take notice.

My initial take has been that banks have a fundamental structural advantage compared to stablecoins that will allow them to maintain their hold on deposits; however, I wanted to challenge my assumption and dig into this topic a bit more. To do so, let’s start with how banks make money and what drives the interest rates they offer.

Bank interest economics

In the classic film It’s a Wonderful Life, the main character George Bailey provides one of the the clearest explanations of fractional reserve banking and how the amplification of the money supply works that you’ll find. Here’s a link to the scene. In the classic model, banks take in a $100 deposit, and then they take a portion of that $100, say $90, and lend it out to other businesses. They then keep a portion, say $10, in reserve so that they have liquidity to fulfill any immediate withdrawal requests. Since the banks are taking on risk by making that loan, they obviously charge interest.

Rather than lending out that money though, a bank could keep all of the funds in reserve, actually putting those funds into a “risk free” instrument like treasury bills. Lending has historically been a more profitable approach to the deployment of deposits than simply plowing money into treasuries. By making a loan, banks are taking on risk. You can upcharge for risk. If you’re putting money into a “risk free” asset, it makes sense that the rate charged would be lower. Of course, the dollar’s recent weakness and questions around the long term fiscal health of the US government are starting to challenge this risk free assumption, but, in general, treasuries have been able to fit the bill of a risk free asset.

In any case, my premise is that a bank with the ability to BOTH make loans and place funds into treasuries should theoretically always be able to offer a more attractive interest rate to depositors since they should be able to charge more interest for making loans.

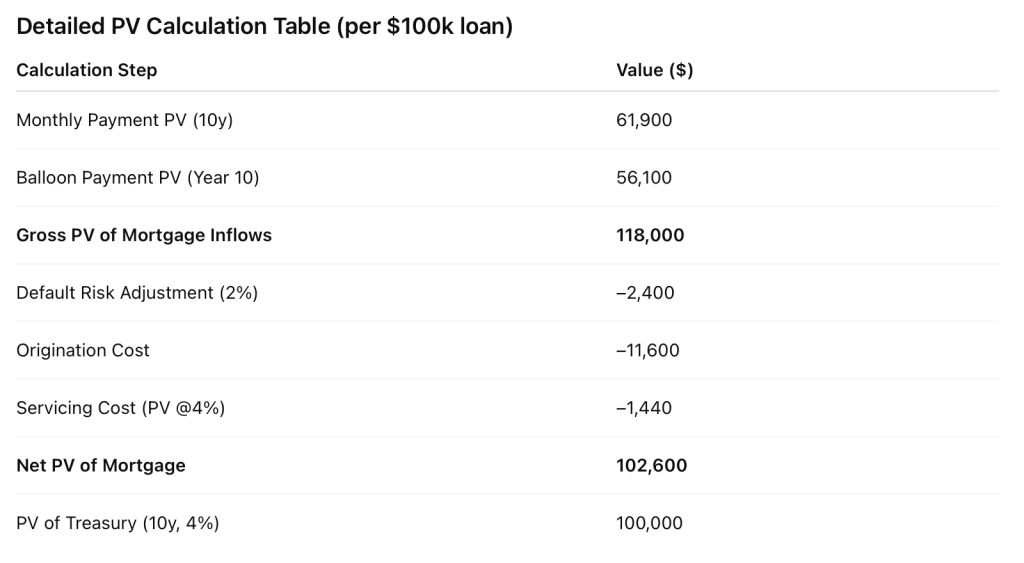

Here is a very simple example putting a $100k mortgage side by side with $100k invested in treasuries. There are a lot of assumptions baked in here, so please note that. There is also another layer with the mortgage resale market, but for now, I just wanted to look at the profitability of originating a loan vs. investing in treasuries. As you will see below, the originating the mortgage loan is modestly more profitable.

Two big assumptions here are default losses and operating costs related to lending. For example, when a traditional bank makes a home loan, there is typically a mortgage banker involved, an underwriter, and some fixed costs like the loan origination software. Rocket Mortgage likely has very different unit economics from the community bank down the road, but the operating costs related to originating the loan eat into the overall profitability of the loan.

On the face of it, you would take an asset yielding 6% (mortgage) vs. 4% (treasury) all day long; however, you have to think about the underlying costs needed to generate those yields. Banks that excel in analyzing risk and streamlining processes obviously have a big advantage.

As I noted earlier, this is a very simple example. The present value calculations I had ChatGPT help me with assumed the risk free rate held constant over 10 years, which is a stretch. There are also a lot of assumptions baked in on the mortgage calculations.

Stablecoins and interest payments

The elephant in the room that I have not addressed is that stablecoin issuers are technically not allowed to issue interest payments according to the GENIUS Act. In practice though, this is happening. It is happening in the form of non-stablecoin issuers providing rewards for holding certain stablecoins on their platforms. Coinbase is the premier example of this, paying rewards for individuals and businesses to hold USDC on the exchange. The crypto exchange OKX just announced something similar with the stablecoin USDG, which is issued by Paxos.

I am sure this is not the last we will hear of these reward schemes. They have flown slightly under the radar, but I imagine the bank lobby is taking a hard look at this. Another way stablecoin issuers are looking at this is to get a bank charter, like Circle is looking at. If “rewards” end up being deemed illegal or are restricted, I imagine you will see more stablecoin issuers apply for bank charters or go out and buy smaller banks to access those charters.

Other levers

In all this discussion around the fight for deposits, there are two other major levers that banks maintain. The first is non-interest income. As I’ve written about, banks have increasingly become reliant on interest income over the previous decades, but banks (especially the big diversified ones) have a variety of fee based revenue products and services. Stablecoin issuers do not (yet).

The second lever is the relationship. This sounds squishy, but I think relationship banking is still a powerful force in local markets. Especially when it comes to home loans and small business loans, having boots on the ground or local area knowledge can help close deals. Once a bank brings in a customer with a large financial transaction, like underwriting a mortgage, there is a major cross-sell opportunity to bring over a deposit or investment relationship as well. After a decade of fintechs unbundling banking services into point solutions, I think many would argue that we have been on a rebundling kick the last 5 years. Everyone from Robinhood to SoFi want to be your one stop shop for all your financial needs. That means it’s not just about competing on rates with one product; it’s about building a suite of products and services that can make you a one stop shop.

More to come on this topic. We need more micro-level analysis on the competition for deposits as stablecoin issuers aggressively push forward, and I’m excited to get further into the weeds here.

Leave a comment