Introduction

A couple months ago, there was some chatter about stablecoins as the solution to the US debt crisis. Paul Ryan penned an op-ed that caused quite a bit of conversation, especially in the crypto world where many have been eagerly waiting for mainstream politicians to finally catch on to the value of stablecoins. Even if you’re a crypto-skeptic, stablecoins (specifically those pegged to the US dollar) offer a compelling narrative when viewed from the lens of US global economic interests.

For a variety of reasons, the US dollar has been the reserve currency of the world in the post World War II era. Global commerce is conducted in dollars. Oil prices and almost all of the world’s critical physical resources are denominated in dollars. The hegemony of the US dollar has largely been tied to the hegemony of the US government, and a faith that the US government will not default on its debt. While that faith has been severely tested in the last decade on several occasions, the US treasury bill remains the safest asset in the world and defines what we call the risk free rate of return (i.e., what return on your money can you receive for taking hypothetically no risk). This faith is rooted in a number of factors, such as military might, technological supremacy, and the centering of capital markets in the US, but fundamentally, it is rooted in a belief that the US government pays its bills. Unfortunately, even without all the political drama taking place in Congress, that belief is being tested by the high level of US debt.

I wanted to take a deeper dive behind the headlines and understand the current state of US debt and how stablecoins fit into the equation of who is purchasing US debt. As I did my research, a few unanswered questions came to the forefront that I wanted to pose and would argue that we need to keep in mind as we digest this narrative of stablecoins as a solution for the current debt problem.

What is the state of the US national debt?

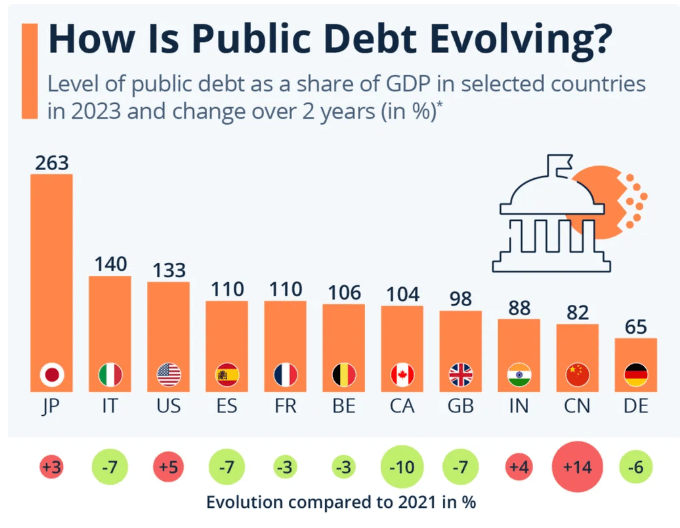

Let’s start by defining the problem though. At the end of 2023, the US national debt was $34T. As you can see in the chart below, that puts the US towards the lefthand side of the chart with a debt to GDP ratio of 133%. Ideally, a country would want that percentage to be in the mid-60% range, and in the EU, member countries are technically supposed to keep this ratio under 60%.

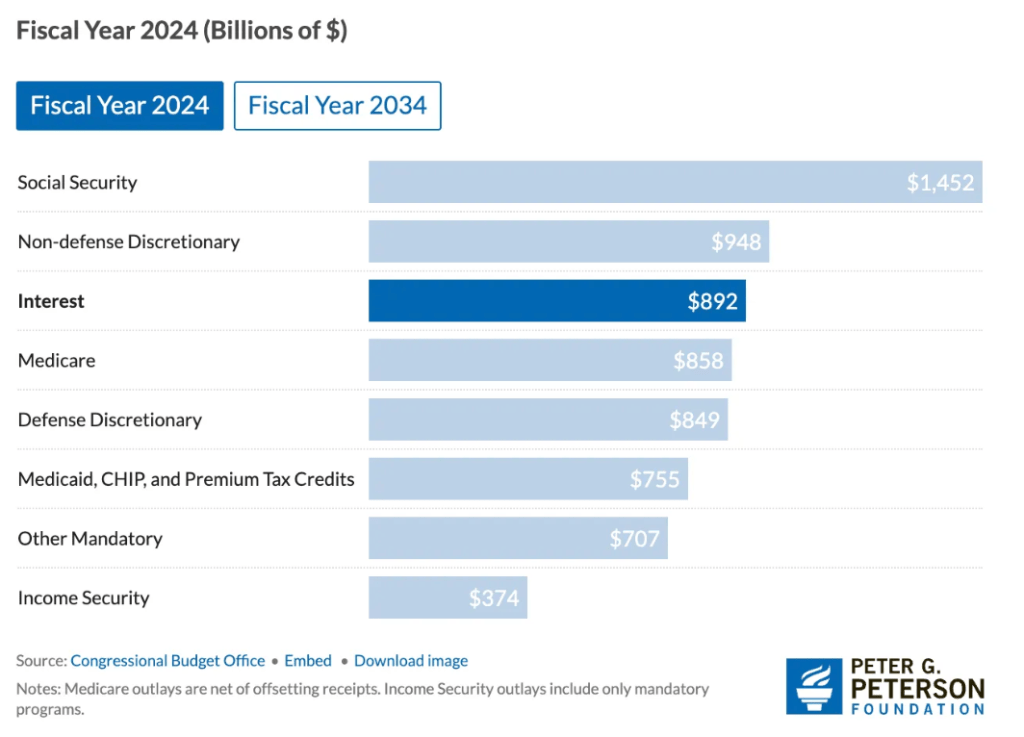

If everyone believes the US will keep paying its debt, is this ratio of 133% really so bad? Unfortunately, the answer is yes. There are a range of reasons carrying such a high debt ratio is bad, but the tangible impact for the average US citizen is that it means the US government spends less on critical things like defense, social services, and education and more on servicing its debt. To drive that point home, see the chart below. the US now spends more on interest payments for its debt than it does on Medicare! That’s scary. And, of course, this is a problem that only compounds (pun intended) as it is not addressed.

Who buys US debt?

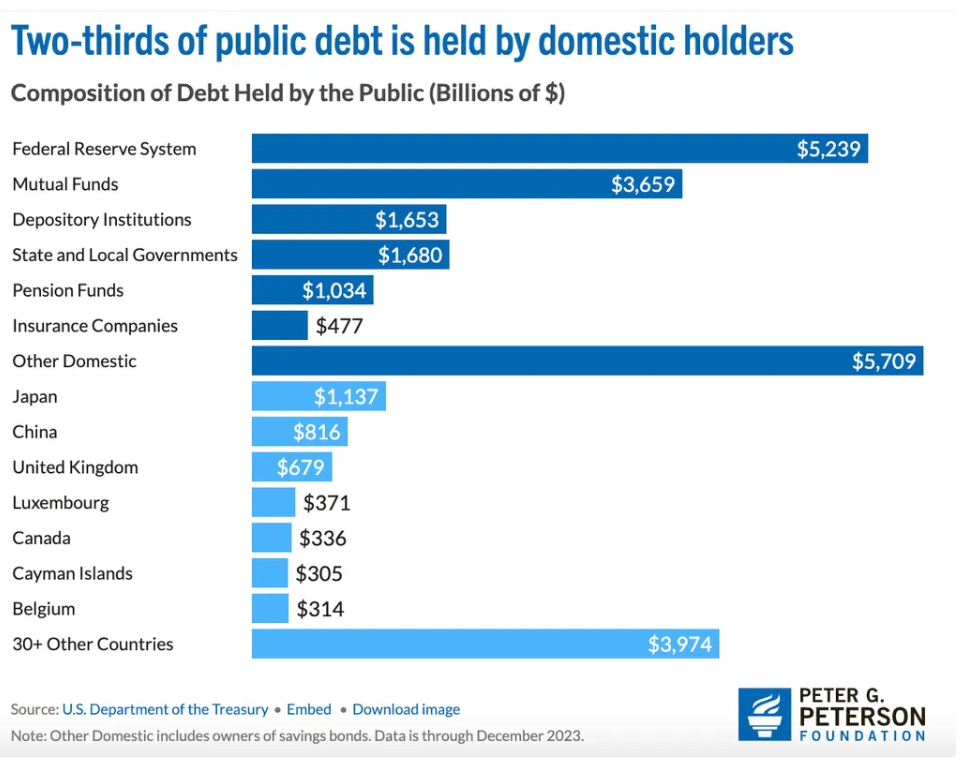

In addition to this crowding out problem where public debt subsumes the ability to spend on other goods and services, there is also an international relations element to this challenge. There is often a lot of chatter in the news about how much US debt China owns. The line of thinking goes that by holding significant levels of US debt, China can exert control over the US economy, and if it decided to rapidly sell that debt, it could destabilize the US and the broader global economy. A massive sell-off of US debt would cause the price of debt to plummet, and the US government would have to offer higher interest rates to find more buyers of its debt. This would accentuate the pain of the current debt crisis.

While this sounds quite scary, there are a few factors at play that have, at least until now, prevented such a scenario from occurring. A significant sell-off of US debt by the Chinese would likely weaken the dollar and strengthen the yuan, hurting China’s large export arm. China is also integrated into the broader global economy, and the fallout from a massive devaluation in US debt would likely cause global turmoil that had blowback for the Chinese economy. Finally, while China’s holdings of US debt are significant, they are actually not the largest holder and hold ~3% of all US debt issued. This percentage had been much higher around 10% before the Fed began aggressively engaging in quantitative easing (QE) post-2008. As the Fed pulls back on QE, China’s share of US debt is likely to rise again, but at the moment, it does seem that any sell-off by the Chinese government could be accommodated by other buyers. There is also speculation that China has an incentive to de-dollarize to ensure it would not be adversely affected if the US were ever to attempt to impose sanctions, similar to how the US has frozen many of Russia’s dollar-based accounts.

As we turn now to think about stablecoins, the chart above gives us a reference point to understand the scale at which stablecoin issuers are buying and holding US debt. We can see above that at the high end China owns $816B of US debt while Japan is the leading owner with $1.1T.

Where do stablecoin issuers fit in?

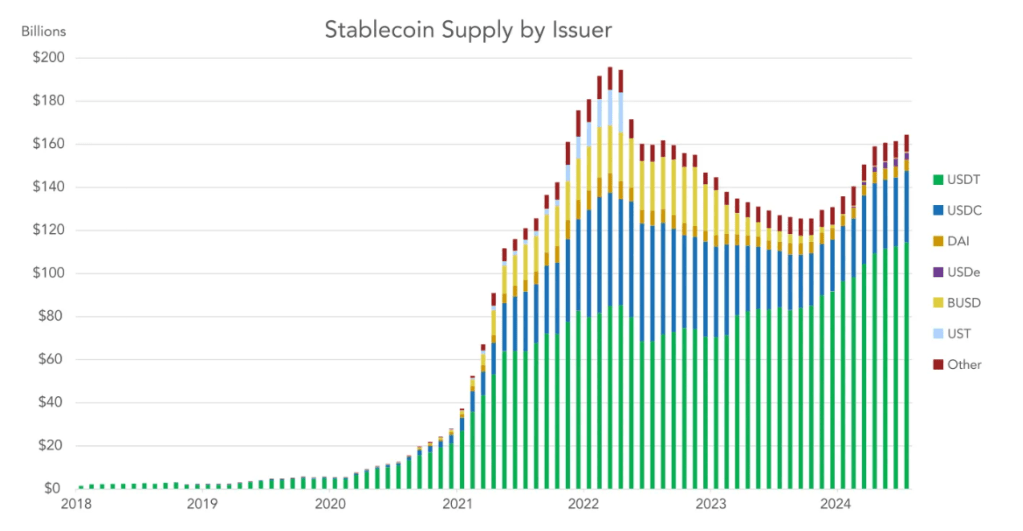

As of September 2024, the current market cap of all stablecoins is just over $160B. As the chart below illustrates, Tether dominates the stablecoin market with over 70% of all issuance being USDT.

When you look at the composition of assets that USDT and USDC hold in reserve, roughly 80% of the reserves they own to maintain their US dollar pegs are US treasury bills. That means that stablecoin issuers own about $128B worth of US treasuries. If you were to consider stablecoin issuers as a country, they would be the 18th largest country in terms of US debt holdings, sandwiched between Saudi Arabia ($143B) and South Korea ($123B). On its own, Tether would be the 19th largest foreign holder of US debt right in front of Germany ($102B).

I’ve seen some news outlets report the ranking to be a bit higher, but I’m not sure how they arrive at that number. Regardless, there’s no doubt that stablecoins are a significant and rapidly growing holder of US debt. While there has been some experimentation with Euro dollar stablecoins and CBDCs, at the moment US-backed stablecoins dominate, representing over 99% of issuance. That doesn’t appear to be changing any time soon.

When you consider that stablecoins have really only been around for about 6 years and had a market cap under $20B just 4 years ago, this is a major new entrant onto the buy side for US debt. Between 2000 and 2010, China roughly 10x’d its holding of US debt. Stablecoin issuers did something similar in a matter of just about a year between 2021 and 2022. The Luna Terra and FTX debacles caused a significant pull back in the broader crypto market, but the stablecoin market cap seems to be steadily marching towards $200B with analysts predicting the market could easily reach $1T in the next couple years.

What questions should we be asking about the role of stablecoins?

I’ve been throwing around a lot of big numbers, but ultimately, what does all this mean? Is it good, bad, or a non-issue for the US economy and government that stablecoins have emerged as significant new buyer of US debt?

The short answer is it’s good. More demand for US debt and US dollars lowers the cost of borrowing and plays a role in slowing the brewing national debt crisis. With that said, I don’t think this issue is as clear cut for the US as saying stablecoin issuers buying US debt is good and China buying US debt is bad. Here are the questions we should be thinking about:

1. Who are the underlying holders of this debt and what are their motivations? At the moment, Tether and Circle are the two major players in the space. Tether is currently sort of a stateless entity, but will it one day be beholden to a certain foreign jurisdiction? What leverage will the US government have over Tether? Obviously Tether and other stablecoin issuers want to operate in the US and tap into the massive market. Therefore, they have mostly complied with US sanction requests and other guidelines, but it is unclear just how far the US government’s oversight of Tether can reach. At the moment, we may feel quite comfortable knowing that the US investment bank Cantor Fitzgerald custodies most of Tether’s assets, but what if that changes down the line. In addition, there is also no trade balance in play. China’s connection to the world economy and reliance on US imports has likely influenced how it has approached any sale of US debt. We will need a new framework for thinking about stablecoin issuers since they are not state entities with trade balances to consider when contemplating purchases and sales of US debt.

2. Does the US really want foreign debt holdings to shrink? Regardless of how much stablecoins grow, there is likely a separate question of how do you keep the world’s second largest economy (China) enmeshed within the dollar ecosystem. Even if stablecoins continue experiencing massive growth, it will be a while before they could fill the shoes of China’s previous proclivity for US debt. It will also be critical to understand how competing foreign-denominated stablecoins or the Chinese CBDC will compete with the dollar ecosystem. Seeing the rise of dollar-backed stablecoins could certainly embolden foreign powers like China to further pursue their own CBDC initiatives and concentrate efforts on building an alternative digital rail for the movement of value that is not reliant on US dollars. This may happen with or without the US embracing stablecoins, but it is certainly something to keep an eye on. Some have argued that the US has “weaponized” the dollar-based financial ecosystem with its use of sanctions. Its logical that foreign powers may be wary of using a digital currency so reliant on underlying assets tied to the US.

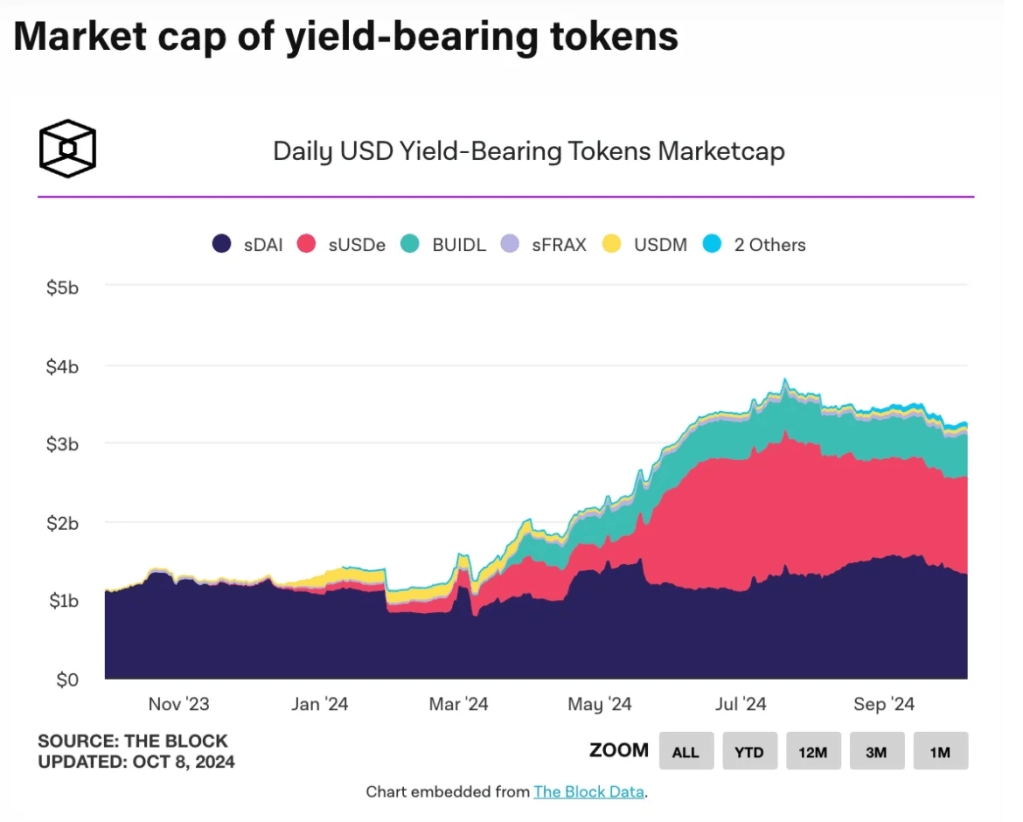

3. What are the underlying risks to the global financial ecosystem by having entities with such high levels of US debt exposure? We all remember the recent banking panic in early 2023 as several prominent US banks melted down as they found themselves with a yield mismatch problem as US interest rates quickly climbed. Two fairly sophisticated mid-size banks, Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic, crumbled in days as they found themselves sitting on piles of US treasury bills that yielded less than the interest rate they promised to pay to depositors. Of course there is more nuance to the story, but these were highly regulated banking entities that ran into challenges managing interest rate movements. Is there a risk that stablecoin issuers grow to a size where they become systematically important and run into similar issues? The immediate rebuttal to this concern is that, of course, USDC and USDT do not offer yield on their stablecoins and likely will not be able to unless they are licensed as banking entities in the US. This may negate the risk, but we need to keep an eye on the proliferation of new yield-bearing stablecoin projects. Most of these are on the smaller end and tend to avoid touching the US market given the potential to be regulated as a security there. This market is small now (see the chart below of the main yield-bearing stablecoins), but this is something to watch closely to ensure a shadow-banking sector does not emerge that could introduce broader risks to the global economy.

4. How do we actually solve the underlying issues fueling the US debt crisis? While stablecoins are far from a panacea, I generally agree with the chatter in pro-crypto circles that stablecoins are a powerful new tool for the perpetuation of the US dollar’s place at the center of the global financial ecosystem. Maintaining this hegemony of the dollar keeps the dollar strong and ultimately helps to lower the US cost of borrowing. Stablecoins are not a long-term solution though. Low borrowing costs are one tool, but more revenue generation and fiscal responsibility are still the key levers for getting the US debt back towards a more sustainable level.

Ultimately, I believe we’re just at the beginning of this story. Right now, this is a niche topic for macroeconomic nerds and crypto enthusiasts, but in the coming years, this will become a mainstream issue. There are muted hopes in the US that we may see stablecoin legislation soon. That will certainly be a step in the right direction as we grapple with this new global force in the US debt market and attempt to understand the implications.

More resources

If you would like to read more, here are some of the resources that I drew on when writing this piece.

- To better understand the reserves backing Tether and USDC, each company offers an audited breakdown of their reserves (Tether & Circle).

- Pomp had a good write up about the Paul Ryan op-ed in the WSJ. Of course, you can also check out Ryan’s op-ed if you’re a WSJ subscriber.

- I relied on the Treasury’s website for recent US debt holding reporting, and The Peterson Foundation was very helpful in breaking down and explaining the US debt levels.

- From what I can tell, The Peterson Foundation is fairly middle of the road in terms of political bias with potentially a slight lean to the right. The stated goal of the foundation is to promote fiscal austerity, and Peter Peterson himself has been critical of policies enacted by both parties that caused a rise in US debt.

- This podcast transcript from NPR is also an excellent primer on the US debt and the role of China.

Leave a comment