Varo Money and Kraken Financial are two of the newest licensed banks in the US. Varo received its license on July 31st, and Kraken followed shortly after on September 16th. The nature of these licenses and the regulatory entities that will be overseeing these two firms are quite different though. As I read the news about these banking licenses, I was unsure about the differences between the two.

Even as someone who formerly worked at a bank, I find the various classifications of banks to be confusing, and I wanted to look into this more. To answer the question above, I’m going to do four things in this post:

- Provide an overview of bank charters

- Discuss the consolidation trend in banking

- Outline the differences in the licenses awarded to Varo and Kraken

- Explain why these licenses matter

Let’s dive in.

1) Bank charters

In the United States, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is responsible for granting national bank charters. The OCC is a bureau within the US Treasury Department. In addition to granting charters, the OCC is also responsible for regulating nationally chartered banks. These are the set of banks that have the “N.A.” after their names, such as JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A.

State-chartered banks are still able to expand nationally, but the OCC is not their regulator. They are regulated at the state level and are also overseen by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The FDIC provides both national and state banks deposit insurance up to $250k per account. Since the FDIC is providing this insurance, they get to take a look around state banks every other year. If a bank does intend to expand across the country, the national charter from the OCC might make more sense. This could reduce the number of regulators the bank needs to interface with since it wouldn’t need to work with regulators in each individual state. I’ve read conflicting takes on this last point though.

I am probably grossly oversimplifying the distinction, but the different regulatory regimes seem to be the biggest difference between state and national licenses. In both license cases, the banks are able to apply for deposit insurance from the FDIC.

The process of chartering banks and the complex map of regulatory bodies could be a post in and of itself. Drawing the distinction between national and state charters is important though because Varo received a national charter from the OCC while Kraken did not. The state of Wyoming issued Kraken’s charter. As we will see, this distinction has implications for what each bank can do and who their regulators are.

2) Bank consolidation

Consolidation in the banking sector has been talked about quite a bit over the last decade. While the number of new banks receiving charters was already on the decline before 2008, the financial crisis caused new approvals to slow to a trickle as this quote makes clear:

“Bank approvals took a nosedive in the last 10 years but are slowly starting to rebound. In 2008, the FDIC approved nearly 100 new banks. By 2009, new licenses granted dipped to 31, before bottoming out at 0 in 2012, 2014, and 2016.”

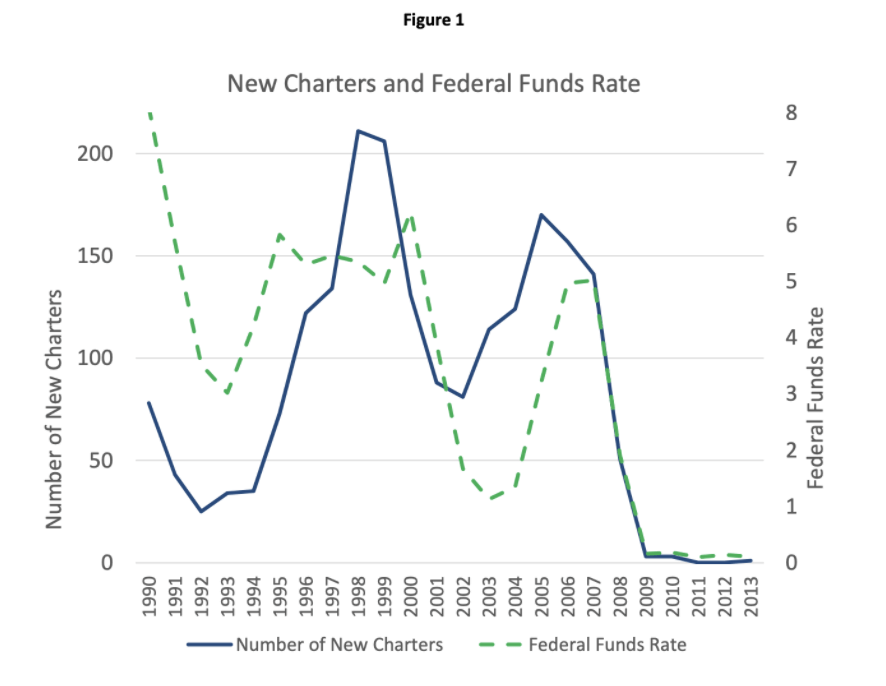

In addition to the financial crisis and the resulting Dodd-Frank Act limiting the number of new banks, we have also seen a lot of mergers since the 1980s following a period of deregulation. Another driver of the shrinking number of banks is interest rate policy. This report from the Federal Reserve is a few years old, but it provides a fascinating look at this topic. The graph below shows the correlation between the level of interest rates and the number of new bank charters. Banks primarily generate revenue from their net interest margin (NIM), so it’s no surprise that in low-rate environments fewer people want to start banks.

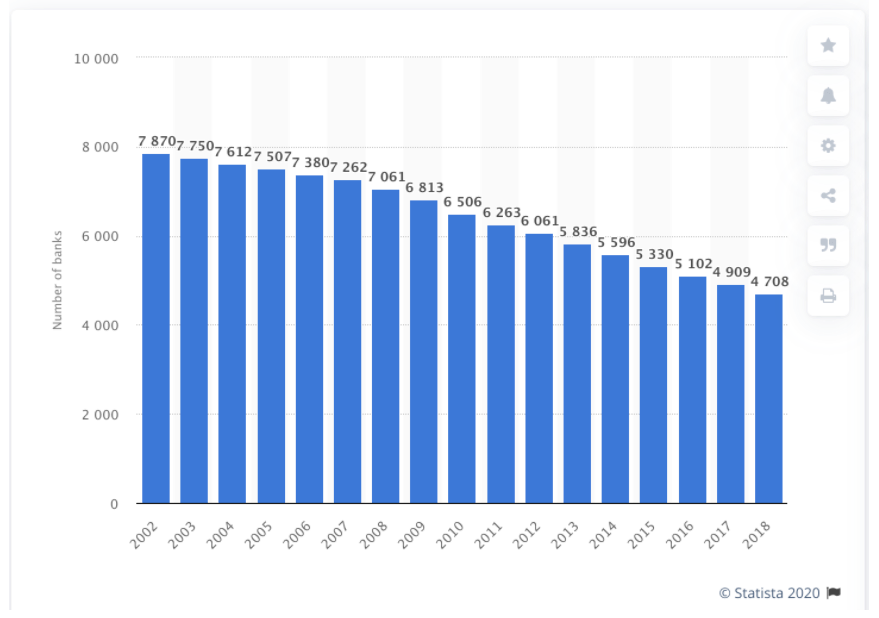

All of these factors come together giving us this second graph below showing the downward trend line in the number of banks in the US. We’ve gone from roughly 8,000 banks 20 years ago to about 4,700 today. This is even more noteworthy when you consider that there were 15,000 banks in the early 1980s.

This consolidation has largely come at the expense of community and regional banks. The chart below is slightly dated, but it shows the trend of deposits flowing towards the top 5 banks in the US while small banks loose share.

I bring up this consolidation trend because it frames the importance of these new licenses and the broader neobank trend in fintech. With current consolidation trends, it had been difficult to fathom how the top 5 banks would not keep dominating the market and grabbing more share. In the last decade, however, fintech banks (another phrasing of neobank) have come onto the scene and started competing for deposits. Lacking bank licenses, these startups partnered with small banks; the fintech with the snazzy UX was the front-end and the small bank with the license was the back-end holding onto the deposits. This formula has worked fabulously for some smaller banks (see Lincoln Savings Bank). This banking-as-a-service (BaaS) trend is definitely not going away, but the licenses for Varo and Kraken have opened up a new pathway for fintechs to challenge the deposit supremacy of Chase, Bank of America, Citi, and Wells Fargo.

3) Licensing distinctions

Let’s start with Varo because their national bank license is fairly straight forward. Prior to receiving approval for the license, Varo had to use the BaaS formula described above. For Varo, the bank behind the scenes was Bancorp Bank. The big task for Varo now is spinning up its own core banking system to manage deposits and migrate customer accounts over from Bancorp, which it apparently started doing in early September.

At the moment, Varo is only offering deposit products, but this is likely to change as Varo will expand into credit products, especially as it seeks to grow the lifetime value (LTV) of the customers it has acquired. Over the long term, running its own banking infrastructure will likely reduce costs, but the real opportunity is on the revenue side where Varo needs to build a broader, multi-product relationship with its customers. My guess is that we’ll see Varo evolve into an institution that looks very much like Ally Bank, a branchless bank offering a full suite of products spanning deposits, credit, and investing.

Turning now to Kraken, its path to becoming the next Ally Bank is less clear, assuming Kraken wants to go down that path. Kraken received a unique state banking license as a Special Purpose Depository Institution (SPDI). The SPDI designation was only recently created by the Wyoming legislature in its bid to attract crypto businesses to the state. Kraken is the first company to be awarded this SPDI license. Many in the crypto world are popping champagne over this announcement, and I think rightly so. The story of the birth of the SPDI is a great example of the private sector working in collaboration with a responsive government to craft thoughtful legislation.

As you can imagine, the SPDI license has some differences when compared to the national banking license Varo acquired. The most significant of these differences is that the SPDI makes it difficult for Kraken to launch a credit product, at least as part of the Kraken banking entity that sits in Wyoming. In accordance with the SPDI, Kraken Financial will need to keep 100% reserves. This means it cannot lend out the deposits it takes in from customers, the bread and butter of most banking institutions. This may seem overly restrictive and a dealbreaker, but it actually has its benefits. The first is that Kraken will not have to apply to the FDIC for insurance. There’s no need to have deposit insurance if you’re not engaging in fractional reserve banking. As a result, the regulatory burden for Kraken will be a bit lighter. Second, this reserve requirement does not harm Kraken’s core business and will likely make its operations more efficient. Let’s unpack this second point.

Lending against crypto assets has a ton of potential, and BlockFi is a clear example of the growth potential of this product; nevertheless, the real pain point in the crypto industry has historically been fiat on-ramps to crypto. If you want customers to be able to trade cryptocurrency, they need a way to change their dollars, euros, and yuan into Bitcoin, Ether, and other cryptocurrencies. This has been really difficult because only a handful of banks will service crypto companies and the regulation around this activity has been unclear. The SPDI will give Kraken access to the broader Federal Reserve payments infrastructure and allow Kraken to more easily facilitate the flow of fiat into crypto. Kraken may miss out on revenue from credit products at the moment, but it’s main revenue drivers are a range of fees on deposits, withdrawals, and trades. The SPDI helps Kraken run these revenue drivers more efficiently without having to rely on third-party entities quite as much. Down the road, there are likely more products Kraken can offer.

There is also a distribution angle here. At the moment, crypto companies are bogged down with state-by-state regulation. There are still some outstanding questions, but state bank charters usually receive reciprocity across state lines, meaning the SPDI should be honored across the US, not just in Wyoming. Ideally, Kraken will now be able to use the SPDI as its foundation to operate across the US and potentially globally. The state of New York is a special case with its BitLicense, disparaged by many in the crypto space, but the SPDI should help Kraken serve clients in most states without needing to have money transmitter licenses in each state. This is a nice quote from Marco Santori at Kraken that sums up this last point:

“Kraken is not a money transmitter. We haven’t sought licenses in the U.S. This [the SPDI] is an alternative path to that, speaking purely from the regulatory perspective. The SPDI charter will help us to satisfy those rules as we seek to bring more and more of the payments flow in-house.”

Ultimately, there is a lot of nuance in the SPDI license. I’m continuing to learn more about it and have found these podcasts from Castle Island and Pomp particularly helpful.

4) Why do these licenses matter?

There are two reasons why this all matters. First, the granting of banking licenses to Varo and Kraken are signals that the great convergence has begun. Over the last couple of years, we’ve tended to place fintech, crypto, and banks into separate buckets. There has already been chatter about consolidation within fintech as SoFi, Lending Club, Betterment, Robinhood, and others have gone from unbundling the bank to now rebundling. Fintechs are rebundling and replicating the traditional banking stack of products under one roof. We’re still in the early stages, but with their launch of crypto offerings, Revolut, Robinhood, and Cash App have shown us this year that crypto is also going to be part of the banking product stack. It is not crazy to think that I’ll soon be using one super fintech app that accepts my direct deposit and auto balances my investment portfolio between stocks, bonds, and cryptocurrencies.

The new licenses only accelerate this trend and open the door for the continued overlap between fintech, crypto, and traditional banks. This great convergence is going to be a slow process, but there is no doubt traditional banking institutions are going to feel more competition as regulatory clarity further enables digital-first offerings.

Following up on that last point, the second reason this matters is that the granting of these two licenses shows that regulation is catching up to technology, at least in the financial services sector. If the US wants to continue being a hub of innovation for financial technology, there needs to be regulatory clarity and rules that foster rather than punish innovation. It’s easy to get caught up in the lovefest that the crypto world has for Wyoming at the moment, but it’s exciting to see the state of Wyoming put the time into getting smart on crypto and then crafting regulation to support the industry.

In some ways, China is already winning the race when it comes to financial innovation and the acceptance of digital solutions. For various reasons, China already has a higher share of digital payment adoption, and super apps like WeChat and Alipay are pervasive. After initial resistance to crypto, China’s central bank is now in the process of experimenting with a digital currency. The US is still the center of the global financial ecosystem, but it cannot sit still. It must continue to put laws in place that foster innovation and position the US to remain at the center of an increasingly digital financial sector.