The 2020 Democratic Primary Race acquainted many Americans, myself included, with the concept of a wealth tax. Storming out of the gate, dominating the policy platform with her oft-recited phrase “I have a plan for that,” Elizabeth Warren explained the concept of a wealth tax in a clear manner. In an piece on the wealth tax, New Yorker writer Benjamin Wallace-Wells quotes Warren, writing:

“’Your first fifty million is free and clear,’ Warren likes to say on the campaign trail. ‘But your fifty millionth and first dollar, you gotta pitch in two cents, and two cents for every dollar after that.’”

Although Warren’s campaign became synonymous with this tax, the Bernie Sanders campaign actually proposed an even more extreme version of the wealth tax, scaling from 1 cent all the way up to 8 cents for the likes of Jeff Bezos. Way back in 2016, the Clinton and Sanders’s campaigns both contemplated adding a wealth tax to their platforms but backed off due to its complexity and the range of other issues already on the table.

Much of the math and economic theory for this tax policy came from three economists. Thomas Piketty wrote the famed book/doorstop called Capital in 2013 tracing the roots of economic inequality. His collaborator Emmanuel Saez and his protege Gabriel Zucman have continued building on the work, and in October 2019, they released their own book The Triumph of Injustice. In this 200 page book, the two University of California, Berkeley, economists take the reader on a quick tour of the history of tax policy in the United States while offering their diagnosis of what has gone wrong with economic equality in the US and how to fix it. While reading a book about tax policy might sound about as fun as a colonoscopy, the book is highly accessible and fast-moving. Even if you totally disagree with Saez and Zucman, they deserve credit for making the topic approachable.

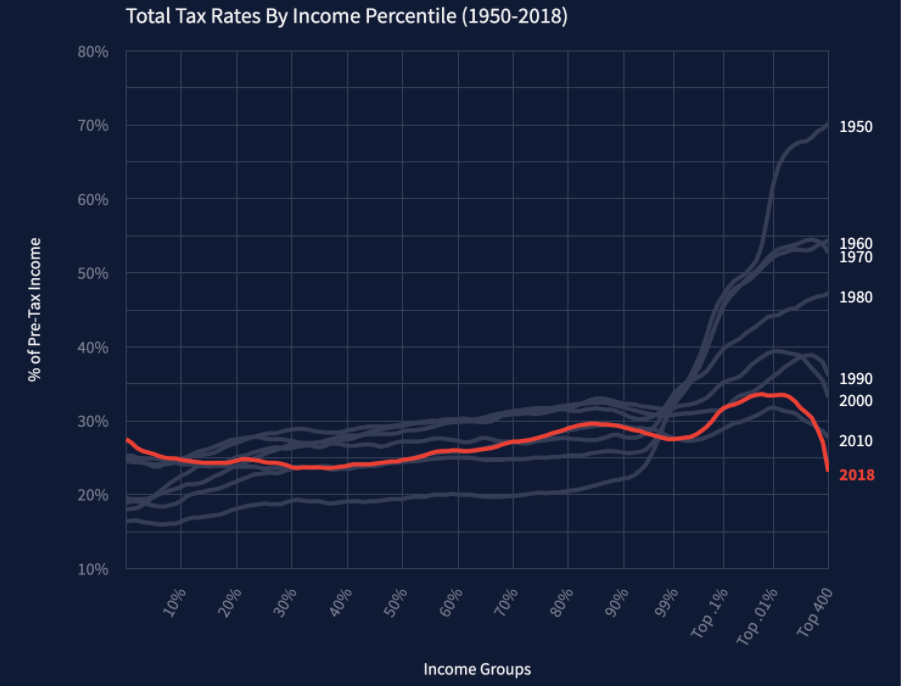

Given my preamble, it is no surprise that Saez and Zucman sit on the left ideologically and believe the US tax system is broken with the rich paying less than their fair share. Cobbling together a variety of sources into a database, they come to the conclusion that the US essentially has a flat tax rate where the mega-rich and the poor pay about the same rate of 28% on their income. Saez and Zucman have put together an online tool to visualize the analysis. The red line below shows the percentage of pre-tax income paid by each income band in the US. The big dip at the end of the red line illustrates that the top 400 income earners in the US pay the lowest rate of taxes.

Progressivity, the idea that one should be taxed more as one earns more, has been espoused as the guiding philosophy of the US tax system for much of the last 100 years. Saez and Zucman’s research and the resulting graph above challenge the notion that the system is still progressive. (As a side note, not everyone is convinced that Saez and Zucman’s calculations are correct, but I will return to critiques later on in the piece.) If we take Saez and Zucman’s data at face value though, then something does seem to be wrong if we want a progressive system and have ended up with that red line above. In my reading, The Triumph of Injustice offers four reasons for why the US tax system has ceased to be progressive. I’ll outline each reason below.

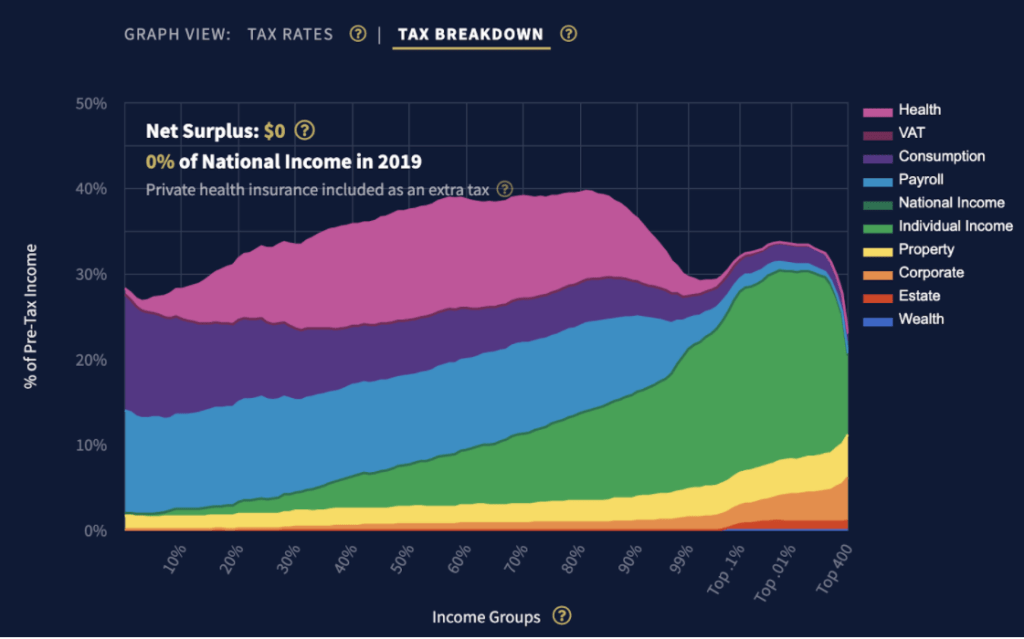

The first reason that the US has an effectively flat tax rate is that state and local income taxes are regressive. I was surprised to discover that one-third of all taxes US citizens pay are state and local. Perhaps if I was a home-owner that would be less shocking. To my mind, much of the political debate around tax policy is centered around marginal tax brackets at the federal level. We argue over whether the top bracket should be 37%, 39%, or higher. That’s all well and good, but tweaking these brackets does little to move the needle. While the bottom 50% of earners pay little or no federal income tax, consumption and payroll taxes drive their tax burden. The graph below is extremely helpful for visualizing which taxes hit each income group. The dark purple-colored wave represents consumption taxes, which are typically levied at the state level.

Sales tax is the same for everyone so as a percentage of income, this ends up eating more income for the lowest earners. This is not rocket science, but this nuance often gets glossed over in political debates. Consumption taxes account for 10% of the income of those in the bottom 50% of wage earners while the corresponding percentage is only 1% to 2% for top decile earners.

The graph above leads to the second reason for the flat tax: payroll taxes. Payroll taxes are actually flat in that the rate is the same for everyone. Every wage earner in America has 15.3% of her or his income deducted from each paycheck. 12.4% goes to Social Security and 2.9% goes to Medicare. Payroll taxes are capped around $130K, meaning that every dollar earned above this threshold does not have the 15.3% deducted. As the graph with the pretty colors shows, there is a lot more light blue towards the left-side and less towards the right where payroll becomes an increasingly small percentage of overall income. In addition to payroll taxes, the authors dedicate some time expounding on how private insurance policies are also essentially a flat tax for the middle class similar to payroll taxes.

Reasons three and four are somewhat related and have to do with different types of income being taxed at different rates. The third reason for the lack of progressivity is capital gains being taxed less than income from labor. Saez and Zucman argue, “…people with the same amount of income should pay the same amount of tax.” This sounds fair enough, but of course, dividends, and realized returns are taxed at a different rate than labor income. Assuming an investment is held for more than one year and we simplify things a bit, that capital gains rate usually maxes out at 20%. The appropriate capital gains rate has been an ongoing debate between Democrats and Republicans. This slightly dated article from the Wall Street Journal offers a solid perspective from each side of the debate. Saez and Zucman take the perspective that income is income and should all be taxed the same. They spend a fair amount of time detailing how capital gains could be more readily accounted for and taxed.

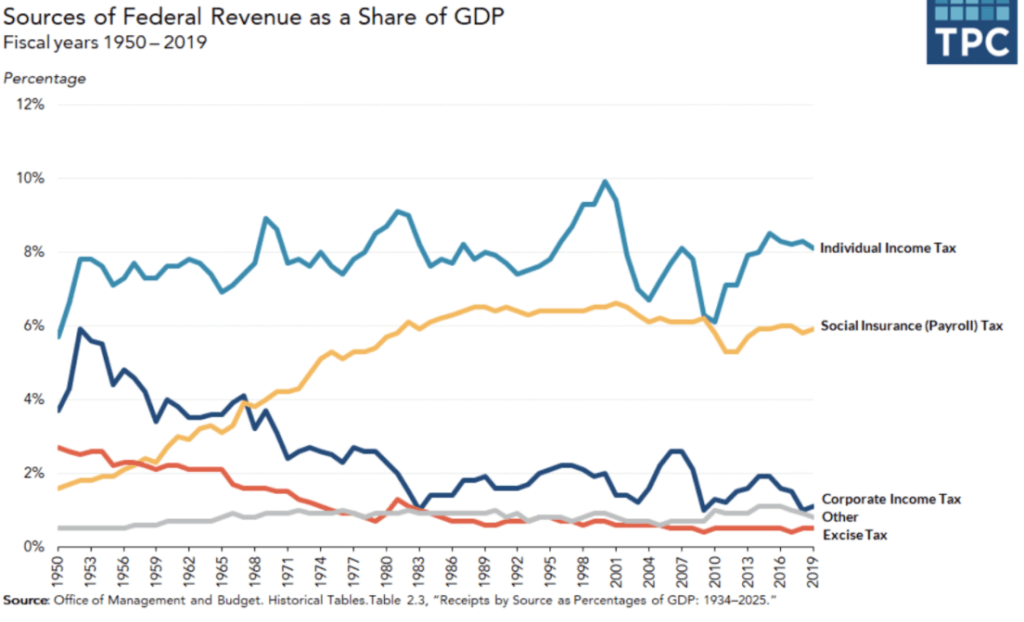

Finally, the fourth reason is the decline in corporate taxation. Since the top income decile of Americans hold the vast majority of ownership in corporate America, any reduction in corporate taxes tends to benefit the most well off. In other words, someone making $20,000 a year is not likely to have a brokerage account where they own shares of Google and benefit from the lower taxes Google might pay. What’s somewhat baffling is that the US had some of the highest corporate tax rates in the world prior to the 2017 Trump tax bill, yet the share of corporate taxation as a percentage of US GDP has been falling since the 1960s as the graph below depicts.

There are a variety of complex reasons for why the share of corporate taxes has declined so much over the last fifty years. Globalization is certainly a key factor with the related phenomenon of offshoring profits. Saez and Zucman spend a fair bit of time haranguing the big four accounting firms and their legions of transfer-pricing professionals for enabling the flight of corporate dollars to tax havens like Ireland and Bermuda.

There are nuances to each of these four reasons; nevertheless, these were the four critical points that stuck with me from the book and explained why the idea of a progessive tax system might be a myth at the present moment. While Saez and Zucman spend most of the book laying out this argument defending their claim that progressivity is broken, they close by offering a range of complimentary policy proposals as a fix. Listening to Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders essentially gives you a sense for what the two economists are calling for, but Saez and Zucman ultimately propose a wealth tax and a significantly higher top marginal tax rate for income at 60%. They are adamant though that any changes must happen alongside beefing up the IRS and pursuing international tax coordination to address the massive challenge of tax avoidance.

I promised I would get to critiques, so here we go. As with Thomas Piketty’s book Capital, Saez and Zucman’s ideas have caused quite a stir in the popular media with the left loving them and the right being highly skeptical of their data and calculations. Much of The Triumph of Injustice is a take-down of Reaganomics, so it is no surprise that the two economists have been embraced by the Bernie Sanders element within the Democratic Party.

Even before turning to the internet for some counter arguments, I had a few critiques of my own. My main hesitation with a wealth tax is its feasibility. Saez and Zucman respond to this critique, writing, “According to our computation, 80% of the wealth owned by the top 0.1% richest Americans consists of listed equities, bonds, shares in collective investment funds, real estate, and other assets with easily accessible market values.” The two go on to flesh out this point, but there is no doubt that implementing a wealth tax would require a lot more resources to both measure the various forms of wealth and curb existing tax avoidance strategies.

Another area of the book where I took pause was the authors’ call for international cooperation around corporate tax rates. I’m of course not the only one who has called out Saez and Zucman for being too optimistic. They call for coordination of corporate tax rates arguing that the US is currently in a zero-sum game with countries trying to out-compete others to offer the lowest corporate rate. It’s a race to the bottom with Ireland and Bermuda leading the way. I completely agree with this point about the zero-sum game, but I’m skeptical the world will get to the point where an across the board corporate rate of 25% is agreed upon. I would want to hear more about what Ireland’s incentives would be for going along with this.

These were my two main holdups, which are reiterated in some of the critiques I have collected below. Garrett Watson of the Tax Foundation has a fairly extensive rebuke where he takes issue with the economists’ proposed high marginal tax rate of 60% arguing that it would crowd out investment. He also calls out Saez and Zucman for only dealing with the pre-tax distribution of income and not accounting for government transfers – the argument being that the tax system becomes fairer when we consider that those towards the bottom receive more benefits like food stamps and Medicaid (another article discussing this issue).

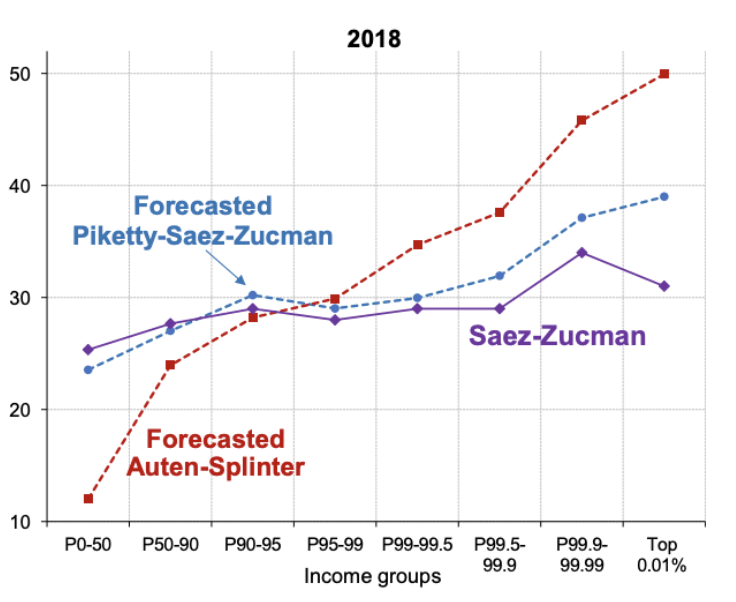

The most rigorous objection to The Triumph of Injustice I have come across so far is from David Splinter, an economist working for the Joint Committee on Taxation in the US Congress. A recent paper from Splinter is quoted extensively in this Wall Street Journal article. In a paper entitled “U.S. Taxes are Progressive: Comment on “Progressive Wealth Taxation,” Splinter goes a step further than Watson and essentially says the extrapolations Saez and Zucman make in their dataset are wrong. While this debate is still ongoing, I wanted to at least highlight Splinter’s findings.

Splinter says Saez and Zucman got three things wrong when constructing their dataset. If one corrects for these three things, he contends that the US does not have a 28% flat tax rate but rather a progressive tax rate (as the red line illustrates below).

The first issue Splinter notes is that Saez and Zucman allocate a greater share of unreported income to the wealthiest Americans than is fair based on historical data. Second, he finds that the Berkeley economists mistreated rollovers when accounting for the contribution of retirement accounts, which artificially inflates the income of the biggest earners. Finally, Splinter believes Saez and Zucman are too generous in an assumption that the bottom 50% of income earners only misreport a tiny fraction of income. Based on IRS findings, Splinter believes individuals in this group misreport roughly $4K in income, which would lower their effective tax rates. Adding these three points together, the crux of the critique is that Saez and Zucman overreport the income of the wealthy and underreport that of the less well off.

To my knowledge, there continues to be a debate as to whose methodology is correct. There does seem to be overwhelming agreement though that historical tax data is a mess and that we need to start collecting better data to analyze.

The Triumph of Injustice certainly will not be everyone’s cup of tea; even moderate Democrats may find its policy suggestions too extreme. Perhaps slightly less controversial is the history of US taxation that the book presents. My favorite chapter in the book was the second where Saez and Zucman sketch a brief history of the twentieth century illustrating how Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt used extremely high marginal income rates to disincentivize profiteering during the two world wars. Prior to this book, I had never realized that the federal income tax did not exist prior to 1913. It was also shocking to discover that since 1913, the top marginal income tax rate has averaged 57%. These are things we are not taught in our US History textbooks, and those of us born after Reagan have never fathomed a top marginal tax rate above 40%.